What is a “good” job?

Work plays a huge role in our lives. Yes, it provides us with money, but work should also meet other needs! A good job provides a sense of purpose, of being useful, of helping to achieve something worthwhile. Good jobs challenge us so that we keep learning and growing. And to help us meet those challenges without becoming overwhelmed, a good job should provide appropriate resources.

Of course, the world of work is more complex than just “good” jobs and “bad” jobs. In many jobs, different projects or tasks might be experienced very differently from one another. This can make it trickier to identify and improve aspects of work that may be undermining what might otherwise be generally positive work experiences.

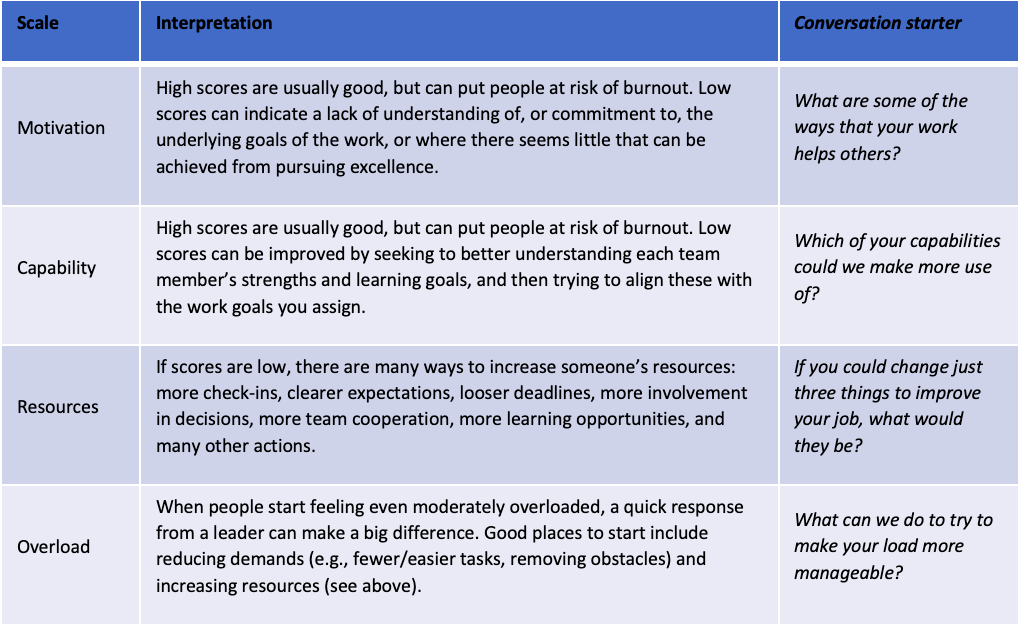

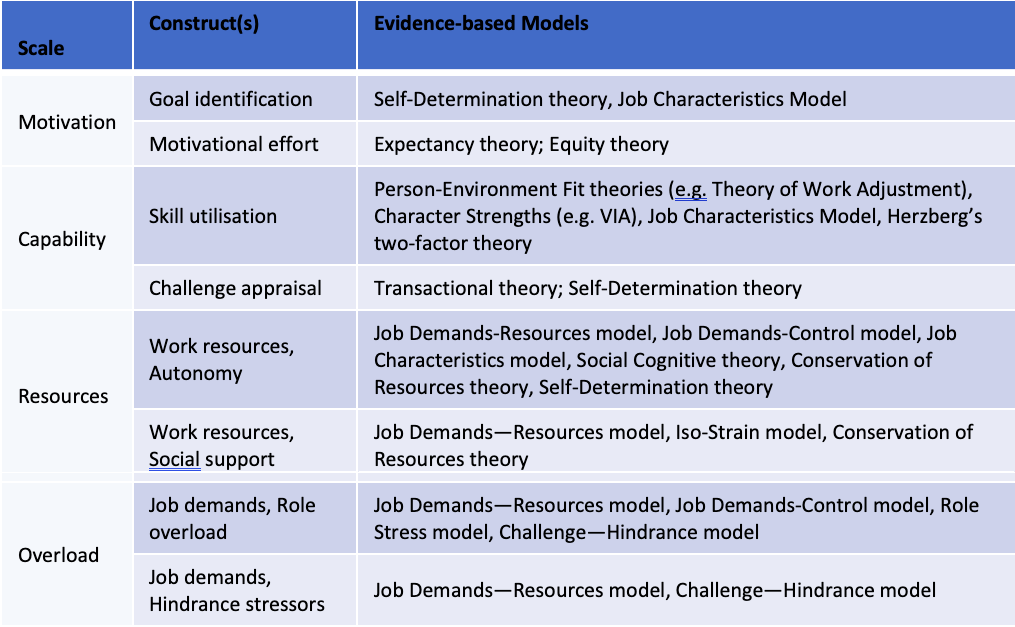

Leanmote measures some key indicators of how people experience their work, and does so in a way that can be linked to specific projects or tasks. Our feedback can therefore help pinpoint which aspects of work are doing well, and which ones could use some attention. Our focal areas are motivation, capability, resources, and overload.

Motivation

What do we measure?

Motivation describes the phenomena behind what we prefer to spend our time doing, how much effort we put into doing it, and how much we persist in the face of obstacles1.

For most work roles, performance quality is more important than quantity. This means that an employee’s desire to excel is an important indicator of motivation to perform. Such desire is uncommon for tasks that seem pointless or arbitrary. People care more about the results of work that seems to support a worthwhile goal. This is why another critical indicator of motivation is an employee’s sense of meaningfulness in their work2.

Although they are complementary, something common to these aspects of motivation is that they are more about an employee’s internal drives (e.g., needs, priorities, goals), also known as autonomous motivations, than they are about external factors (e.g., bonuses).

Why measure this?

The forms of motivation that we measure are highly relevant for work performance. All else being equal, a person who is more motivated will usually outperform someone who lacks motivation1,2. People tend to feel their most motivated about things that connect to their internal drives (e.g., needs, priorities, and goals)3. These internalised forms of motivation appear to be particularly important for performing well at complex tasks4.

However, these internalised motivations are also important for employee wellbeing. Employees who experience more internalised motivation tend to report more satisfaction, more engagement, and better wellbeing than those lacking such motivation4. By providing conditions that fuel such motivations, employers are more likely to create environments in which employee wellbeing flourishes.

By tracking motivation, people can develop insight into the types of tasks that connect best with internal drives. Managers can learn how to better match assignments to team members on the basis of motivations, and to provide feedback that supports motivational needs. Clients of LeanMote have access to guides for using feedback to address unfavourable results.

Capability

What do we measure?

Your people are likely in their current roles because they have valuable skills. But to make the most of your people, and to help them get the most out of their opportunities, you need to think about how their skills are utilised and developed.

We feel more capable, and our work seems more meaningful when we have more opportunities to use those skills we invested time and effort developing to a high level2. Similarly, when our work makes use of our personal strengths and qualities that we like about ourselves, we tend to feel more confident and optimistic5. By contrast, when we’re performing simple tasks that anyone could perform, we feel less useful and less unique. And people can feel threatened when performing tasks that accentuate their weaker areas.

But if we rest on our laurels, doing the same things again and again, then we eventually lose enthusiasm, even if our tasks are a great match to our skills. This is why it’s also important to develop and challenge people. When handled correctly, opportunities to learn and achieve more are experienced as positive challenges that facilitate engagement, problem-solving, and healthier responses to stress6.

Why measure capability?

It’s good practice to put your employees’ strengths to good use. Several theories of work psychology emphasise the importance of achieving a good fit between task requirements and employee character strengths5 or capabilities7. Studies show that employees tend to have more positive attitudes when they have more opportunities to apply more of their strengths, utilise more of their skills, or develop their skills5,6,8. Put simply, employees are happier and more motivated when they get to do more of whatever they are good at, or when they can further extend their capabilities!

By tracking capability over time, it will be easier to identify where capabilities are well matched to tasks, and to plan development opportunities that support ongoing fit. Managers can learn how to better match assignments to team members on the basis of capability, and may be able to allocate resources to support those for whom the match is less suitable. When handled well, stretch goals, complex tasks, unfamiliar situations, and higher levels of responsibility, in addition to more conventional learning opportunities, can all work to enhance capability, ultimately contributing to a sense of growth and mastery. Clients of LeanMote have access to more detailed guides for matching challenges to employees.

Resources

What do we measure?

No-one is an island. Good work requires motivation and capability, but it’s hard to excel when you lack the necessary resources. In this context, the term “resources” applies to a wide variety of things that people can use to improve their performance and to better handle the day-to-day demands of work. Resources can be such things as reliable technology, efficient processes, accurate information, clear goals, and more9.

The two complementary resources we focus on are autonomy and co-worker support. When people have autonomy, the freedom to decide how they can best achieve goals, they can better manage their other resources and they feel more ownership of any achievements they produce9. When people can rely on their leader and peers for assistance, advice, and emotional support, they can draw on more knowledge and experience and they are less likely to become overwhelmed9.

Why measure resources?

Higher levels of work resources, particularly autonomy and co-worker support, are consistently associated with higher levels of job satisfaction and employee engagement9. People with better work resources also tend to report lower stress and burnout9.

In some jobs, resources will vary from task to task. In some contexts, people may come to expect poor resources and may not think to ask for them. By tracking resources, managers can identify resource needs and offer to provide them without waiting until work falls behind schedule. Clients of LeanMote have access to more detailed guides for using feedback to address resource limitations.

Overload

What do we measure?

Overload occurs where someone finds themself expected to do more than can be accomplished in the available time frame. This can be a consequence of poor time management, but overload can arise for many other reasons, including but not limited to misjudgements of task complexity, impacts from unforeseen events, or a simple lack of personnel.

Overload can also be triggered or exacerbated by hindrances, things that interfere with efficient achievement of our work goals. Some examples include upstream process delays, flawed systems, bureaucratic hurdles, ambiguous requirements, conflicting priorities, and tensions between staff members.

Why measure overload?

Work overload is one of the best predictors of employee stress and burnout9,10. Hindrances, such as ambiguity and conflicting priorities, also consistently predict stress and burnout10,11. Hindrances can also harm work performance at least as much as overload (if not more12). So it’s in an organisation’s best interest to avoid these!

However, it’s often difficult to identify overload. For employees, admitting to being overloaded can be confronting in an environment where everyone seems to be managing heavy loads; it can feel like admitting that you lack capability. Yet employees can become overloaded despite being highly capable and motivated. For a manager, it can be hard to anticipate just how much a given task will impact an individual’s workload, particularly when employees are working across multiple tasks and projects.

By tracking experiences of overload, employees can develop insight into the types of tasks that they are most likely to find overwhelming. Managers can use this information to better allocate resources, since high levels of resources help to prevent overload or mitigate its effects8. Here in particular, early responses to increasing overload are likely to make a big difference. However, as even a well-resourced employee can become overloaded, clients of LeanMote have access to more detailed guides for using feedback to address unfavourable results.

References

- Vinacke, E. (1962). Motivation as a complex problem. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 10, 1-45.

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldman, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250–279.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005), Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362.

- Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Washington, DC: APA Press.

- Searle, B. J., & Tuckey, M. R. (2017). Differentiating challenge, hindrance, and threat in the stress process. In M. P. Leiter & C. L. Cooper (Eds) Routledge Companion to Wellbeing at Work (pp. 25-36). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Dawis, R. V., & Lofquist, L. H. (1984). A Psychological Theory of Work Adjustment: An Individual-Differences Model and its Applications. University of Minnesota Press.

- Morrison, D., Cordery, J., Girardi, A., & Payne, R. (2005). Job design, opportunities for skill utilization, and intrinsic job satisfaction. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14(1), 59-79.

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273-285.

- Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123-133.

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834-848.

- Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta‐analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61(2), 227-271.